Gray Whale Watching Guide

Gray Whales: Eschrichtius robustus

Gray Whales are mammals that belong to the order of Cetacea which means “sea monster”. Within the order of Cetacea there are two suborders: Odontocetes and Mysticetes. Odontoceti means “toothed whale”, while Mysticeti means “mustached whale”. Some examples of toothed whales are Sperm Whales, Orcas, Dolphins, Porpoises, etc. Mysticetes include Gray Whales, Blues Whales, Humpbacks, Fin and Minkes, etc.

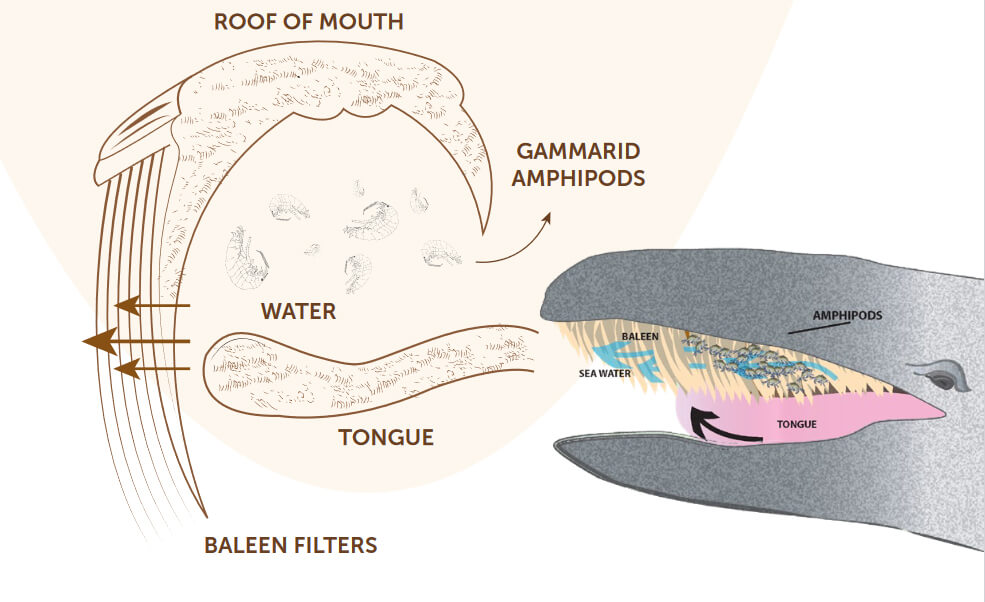

There are a few major differences between these two suborders. Odontocetes whales have teeth in which to catch their prey, such as fish and squid. They also have only one blowhole on top of their head in order to breathe. Mysticetes whales are known as baleen whales. Baleen whales have two blow holes. They have no teeth with which to feed. Instead, they have a keratin filter, called baleen, which hangs from the roof of their mouth.

Keratin is the same material our hair and nails are made of. The baleen hangs in the formation of vertical plates and acts as a giant sieve. Baleen whales take a large mouthful of ocean water in order to filter out prey such as plankton, krill, fish and other organisms. Since they are mammals, like us, if they drink too much salt water, they will dehydrate. That is why they utilize the baleen sieve, to maximize their caloric intake and decrease the amount of salt metabolized.

Baleen Filtering

An Amphipod

While in their northern Arctic home, Gray Whales feed for approximately five months on mud-dwelling creatures called amphipods- a shrimp-like animal. During this time they may consume up to 67 tons of amphipods and other small invertebrates before heading south for reproductive purposes.

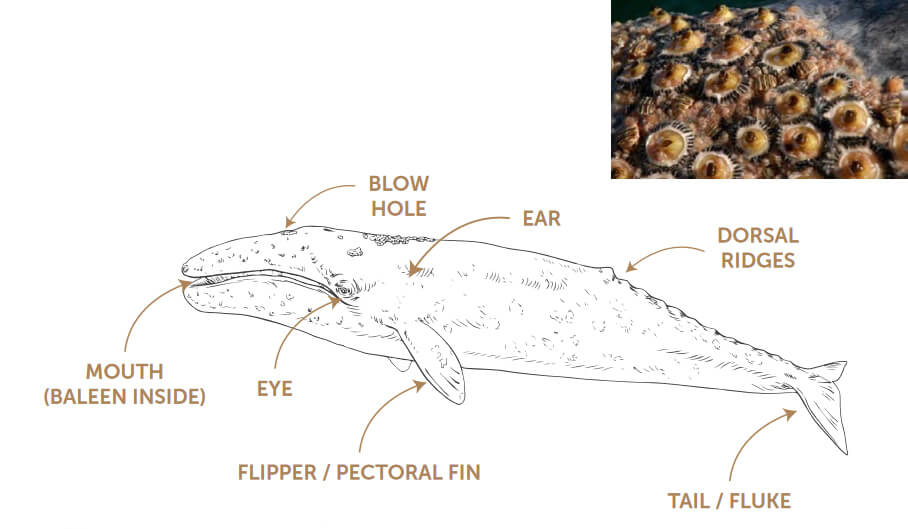

Gray Whale - Identification and Size

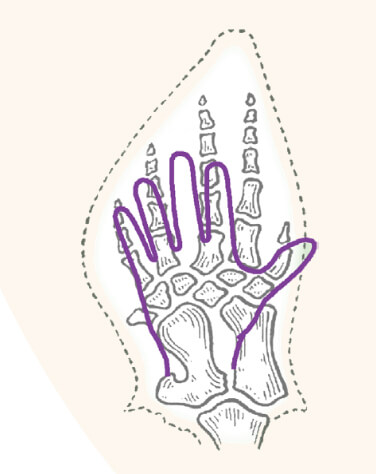

Gray Whales belong to the suborder of Mysticeti and are in a family of their own, Eschrichtiidae. They are mid-sized whales reaching lengths of 35-50 ft (11-16 m), and weighing up to 40 tons or the equivalent of 10 adult elephants. They have pectoral flippers, which contain similar arm, wrist and finger bones that we have.

Many whales have a dorsal fin on their back, but Gray Whales have only a small rounded bump followed by a series of gradually smaller dorsal bumps called ‘knuckles’. Like all Cetaceans, Grays have a fluke, or tail that is made of cartilage, like our ears. Since Gray Whales are baleen whales, the females will grow larger than the males. Within Odontocetes (toothed whales), the males grow larger than females.

Gray Whales are dark gray in color with mottled white, blotchy skin. One reason for this discoloration are the parasites that live on their skin. They also have crustaceans called barnacles that embed their shells into the skin of the whales. These barnacles hitch a ride from the Grays. As the whale swims, the barnacles stick out their appendages to collect plankton to feed themselves. The particular barnacles found on the Gray Whales are species specific, living on no other organism. The barnacles die and fall off the whales, leaving a white scar. Living amongst the barnacles are a type of cyamid known as whale lice which are pink-orange in color. The lice have the special job of feeding on the whale’s dead skin. The calves will receive the lice from their mothers during nursing. An adult Gray may have up to 100,000 varying sized lice on their skin.

Length: Up To 50 Ft

Length: Up To 50 FtWeight: Up To 40 Tons

The Journey of the Gray Whale

Over a period of approximately three months, Gray Whales travel along the coast of North America to the shallow breeding lagoons of Baja California, Mexico. Gray Whales average 80 miles a day at an approximate speed of 5mph. It is believed that Cetaceans are able to shut down half of their brain to sleep while they continue swimming. Considering they are conscious breathers, they need to think about every breath. While one half of their brain is resting, the other half is aware enough to breathe. In this case, the whales are able to continue swimming on their migration route and take short naps along the way. Upon arriving to the lagoons of Baja, Mexico, they may stay for as little as a week or for a period of up to two months. They then turn around and make the return trip to Alaska. Round trip is approximately 10,000 to 14,000 miles! In the warm water lagoons of Mexico, we see the single adults first, that arrive to mate, followed by the pregnant females soon to give birth in the protective shallow water lagoons. Although the juveniles migrate, many have no reason to go to the southern lagoons of Mexico and will often turn back towards Alaska before the adults. This may just be an evolutionary need to make a practice run.

Gray Whales have a specific range and predictable migration pattern. During the summer months they feed in northern Alaska in the Chukchi and Bering Seas, in and around the Arctic Circle.

Back From the Brink of Extinction

From the 1840s to the 1940s, piles of bones littered the shore of the Mexican breeding lagoons as Gray Whales were killed for commercial uses. Whalers discovered these sheltered breeding and nursery areas in the mid-1800s, and over the course of the next century killed thousands of whales, decreasing their population from an estimated 24,000 to only a few thousand individuals. They were finally given protection in 1946, and over the last half century their numbers have increased to over 20,000. California Gray Whales are no longer considered endangered, and on June 16 1994 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) removed the eastern North Pacific stock of Gray Whales from the U.S. List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. However, they are still protected under the US Marine Mammal Protection Act, prohibiting anyone from harassing or hunting them.

Mexico: First to Protect Gray Whales

San Ignacio Lagoon is part of the Vizcaino Biosphere Reserve, established by Mexico in 1988 and is the last undeveloped nursery and breeding ground in the world for the Eastern Pacific Gray Whale. This pristine lagoon is also a critical habitat for the near-extinct prong-horned antelope and an important environment for a variety of sea turtles, bottle-nose dolphins, numerous bird species, approximately 60 other animal species, and 14 plant species.

Life of a Gray Whale

While in Alaska, the mother weans her calf and teaches it how to feed on invertebrates from the mud. After the two split, the mother Gray will return to the Baja lagoons and most likely become impregnated again. She therefore gives birth every other or every two years for the rest of her life. Females average 30-35 calves over their lifetime!

Scientists estimate the average Gray Whale lives 70-80 years. We do know that Grays mature between the ages of 5-10 years. The gestation of a female lasts 12-13 months, giving birth to a 15 foot, one ton calf. That calf will stay with its mother for the first year of life, after which they are considered solitary animals. The calf nurses on 50% butterfat and gains up to 150 pounds a day. Cows milk contains approximately 4% butterfat.

Survival of the Fittest

The main predators of Gray Whales, besides humans, are Orcas. Many marine mammals are in fear of killer whales, the top predators in the ocean. Orcas are considered “wolves of the sea”. It is thought that one reason the Grays are coastal migrators is to hide behind rocks and kelp along the jagged edge of North America. This may also be a reason why the Gray Whales prefer the lagoons of Mexico, Orcas typically will not enter these shallow lagoons for fear of beaching themselves. It is well documented that when Orcas attack, they prefer to drown the calves and stay clear of the mother’s powerful fluke that can easily kill or injure the Orca. After the Gray Whale is dead, the Orcas eat the fatty bottom lip and tongue of the Gray. Everything else is left behind. Who would want to eat through a foot of blubber just to get to the meat? We do see many whales with “rake marks”. This is caused by the teeth of the Orca raking across the skin of the Gray as they try to slow them down. Most rake marks we see are on the fluke, or tail of whales. We are usually happy to see a whale with these scars, because we know that they have survived! And are experienced in avoiding these predators of the Sea.

Behaviors

While watching Gray Whales you may predict their swimming pattern. Usually they will be at the surface for 3-5 breaths, re-oxygenating their blood. Whales are able to utilize about 90% of their oxygen in every breath. Humans on the other hand only exchange about 15-30% per breath. On a deeper dive, Gray Whales may raise up their fluke. An average Gray Whale dives for 5-7 minutes while having the ability to dive for up to 20 minutes. Most dives of a Gray Whale stay within 200 feet of the surface. They do not need to dive deep while traveling and they feed in water that is fairly shallow. It is possible to see Gray Whales anywhere along their migration route in the fall and spring since they are coastal migrators. They exhibit a variety of behaviors which are easy to identify. The average whale watcher will see the most common of behaviors: the whale’s BLOW, the whale swimming and FLUKING. Occasionally we may see them BREACH, perform COURTSHIP or MATING. While in the breading lagoons we usually see lots of BREACHING, COURTSHIP, MATING, SPYHOPPING, NURSING, FLUKING and the ever-not-so-common feeding in the shallows.

MATING:Self explanatory... in some cases you may see “Pink Floyd”... be prepared!

NURSING:

The calf goes under the mother to nurse; occasionally the milk may be visible in the water. Often the calf will come up for breath on opposite sides of the mother during the process.

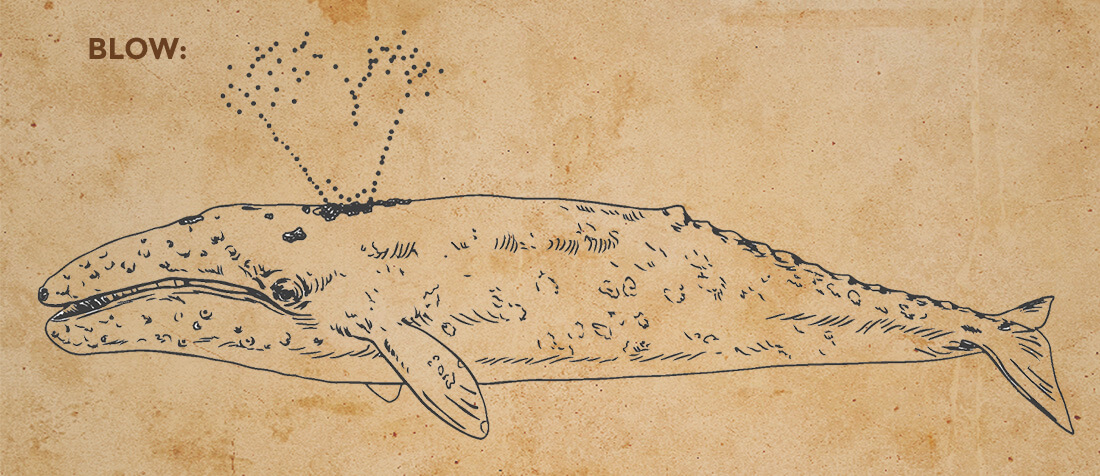

BLOW:

The whale’s exhale breath. Mostly warm air escaping from the blowhole on top of the whale’s head. This is similar to breathing out on a cold day and seeing your breath. Gray whales have a characteristic heart-shaped blow, expelling up to 100 gallons of air!

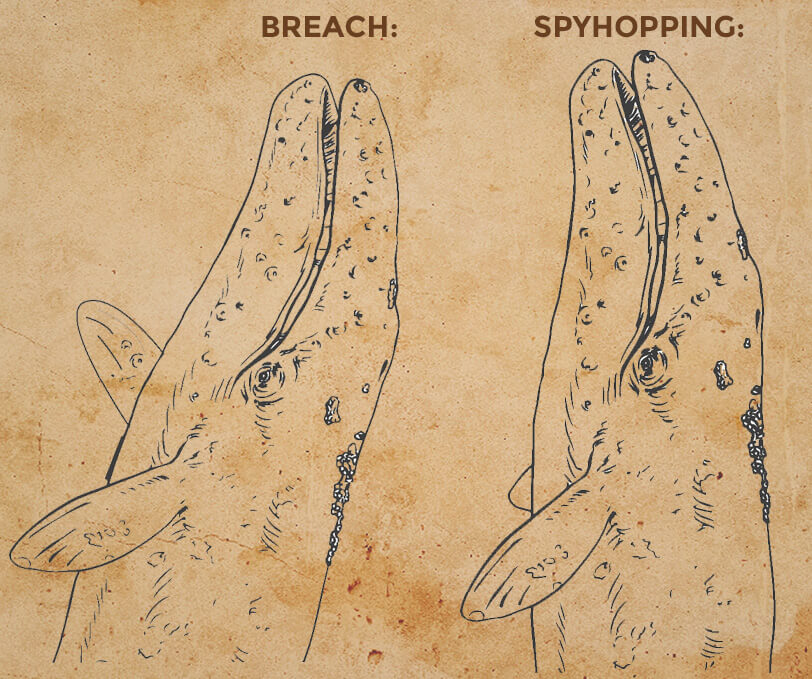

BREACH:

BREACH:The whale launches itself out of the water. Usually the head and flippers are seen and occasionally the entire body.

SPYHOPPING:

The whale vertically lifts its head out of the water to ‘take a look around’. Some times the eyes maybe visible on the side of the whale’s head.

FLUKING:

FLUKING:As the whale goes down on a deeper dive, they raise up their tail or FLUKE to get an extra push off the surface of the water.

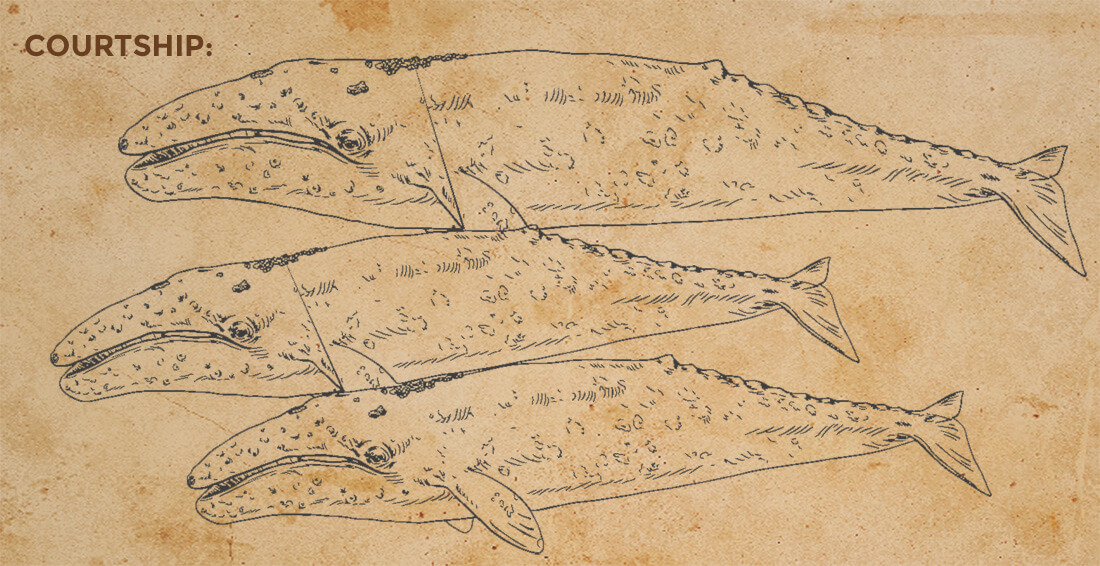

COURTSHIP:

COURTSHIP:Two, usually three plus whales rolling around belly to belly. These are most likely two males and a female. It usually looks like an underwater ballet.

The Friendly Gray Whales of San Ignacio Lagoon

Gray whales are also very well known for their “Friendly Behavior”. This is very common in the lagoons of Mexico. It started in Laguna San Ignacio in 1972 with fisherman “Pachico” Mayoral. His fishing boat was surrounded by Gray Whales and he felt compelled to reach out and touch one. That began the legend of the friendly behavior towards humans. From that point Grays have become friendlier each year and you can witness mother Grays pushing their calves to the small fishing boats to experience this intimate first contact. This behavior only known to San Ignacio Lagoon has since spread to other lagoons. In any case, the behavior is primarily in Mexico and IT IS ALL ON THE WHALES’ TERMS!

They choose to come to our little pangas, or fishing boats. They choose to lift their heads out of the water and some times they choose to allow us to touch them! It is always important to keep away from their eyes, blowhole, flippers and fluke! These are very sensitive areas. It is definitely an amazing experience that is difficult to put into words.

There are these huge, wild creatures slowly approaching our little boats and all they want to do is be touched. The most amazing experience is to reach out to a one month old calf that is being supported by its mother. You reach out to touch it, as you do you look down and notice the calf is looking into your eyes! It is almost like they are bridging the gap between the species. We are ALL animals, right?

When to See Gray Whales in Baja Mexico

Gray Whales make their annual migration to Baja, Mexico beginning mid to late September as they leave the Alaskan region and the waters of the Chukchi and Bering Seas. While their migration takes them along the western coast of the United States at a pace of approximately 80 miles daily, not all of the Grays make the full migration to Baja, Mexico. Those that do make this arduous swim south come for a very specific reason. They arrive Baja’s warm water lagoons to mate and give birth.

It is typical to see the first of the Gray Whales arrive the Gray Whale Breeding Lagoon’s mid December. As each week passes, more and more Gray Whales arrive the lagoons. These first Grays to arrive are typically adults that come to mate. As the season progresses, more whales fill up the lagoons January and February. By early to mid February we see some of the first born Gray Whale Calves. By mid March the lagoons are usually filled with adult mother Gray Whales with their calves. Mothers train their calves by swimming up and down the lagoons or outside the lagoons daily to build their strength in order to get them prepared for the enormously long norther migration they are soon to face. Many of the mother Gray Whales will stay in the lagoons until early to mid April before they take their calves on long migration north.

So in short, you can see Gray Whales in Baja’s Lagoons beginning mid December through mid April. However, based on numerous years of taking census’ we suggest the Gray Whale season is from mid January through mid April with the bulk of the season from early February till early April.